A Language and Mini IDE

This is the first article in a series documenting my practical investigations into agentic coding.

In many ways it’s the odd one out: it spans several years of me intermittently picking up my compiler project, testing the AI coding tools of the moment, and trying to understand two things—how to work with these tools optimally, and how much trust (or caution) they deserved both immediately and over time.

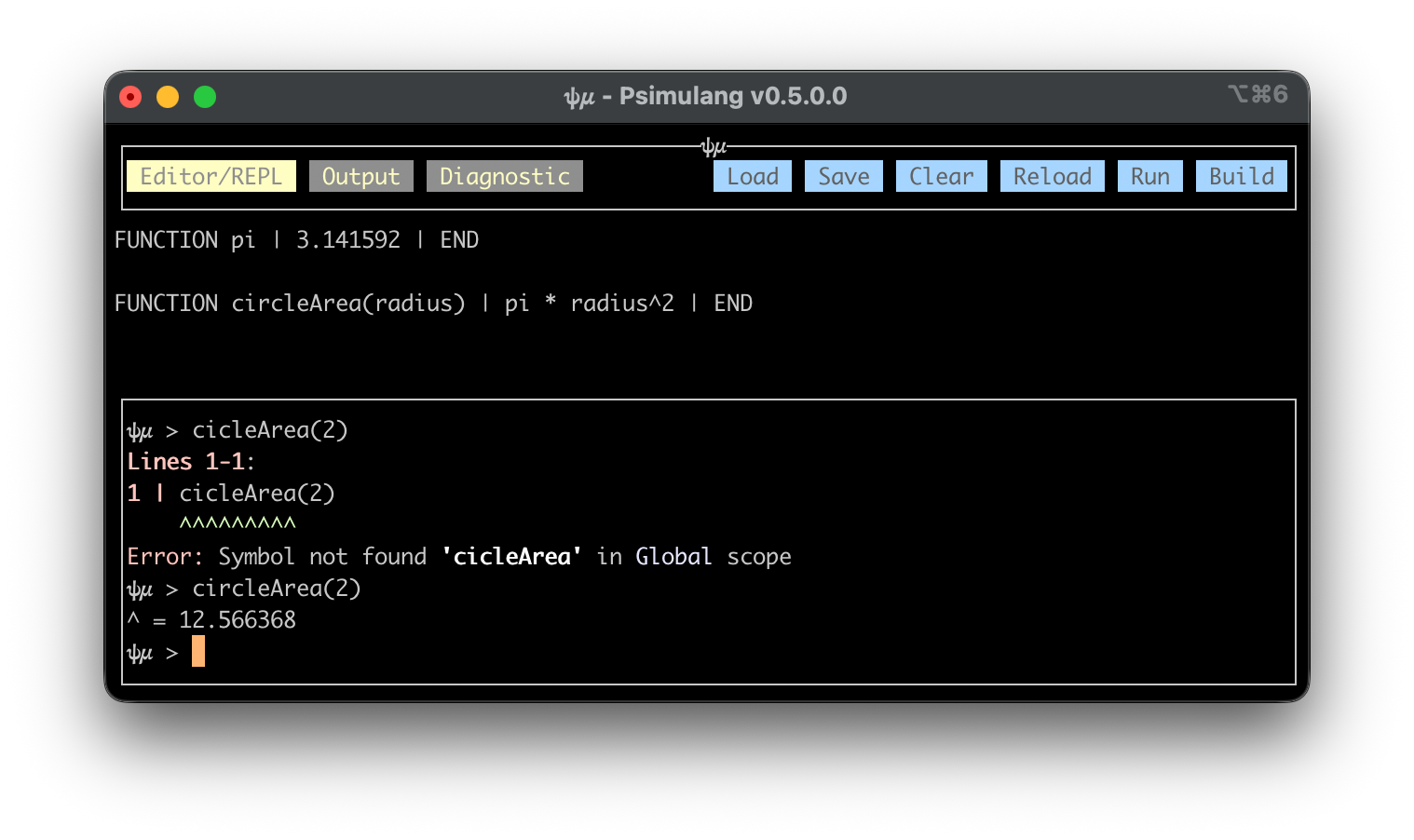

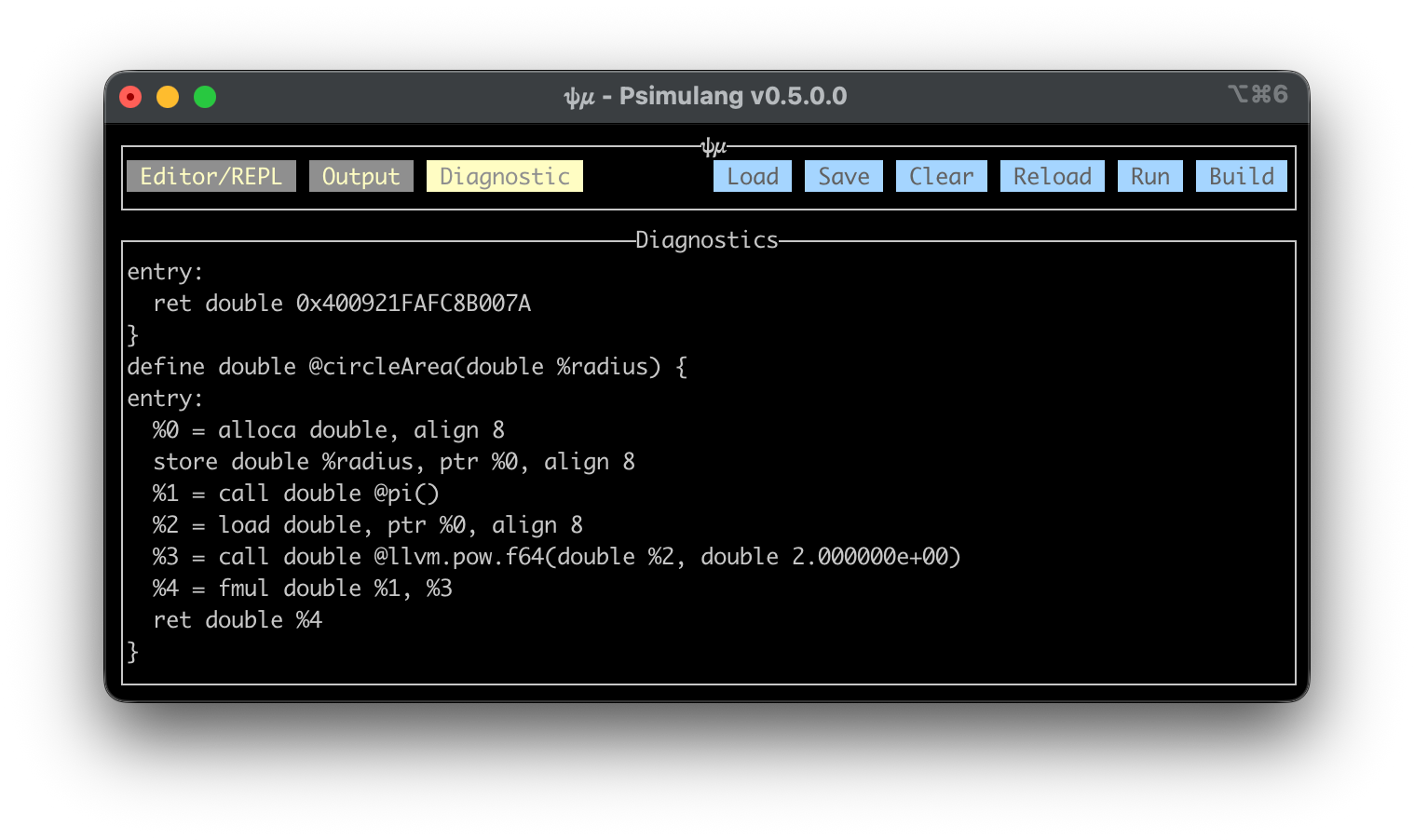

The compiler project itself has been something of a long-running companion. It began life as a minimal LLVM front-end for a tiny expression language. Over time it accumulated various bells and whistles, and recently I returned to it with more serious intent: I wanted to explore agentic scripting in a deliberately simple language, with just enough type information to provide meaningful static guardrails and, crucially, a semantic analyser capable of offering high-quality hinting. My hypothesis was that simplicity is generally an LLVM-friendly property, and that such hinting could be extremely valuable in an agentic loop whenever the LLM fails to “one-shot” the correct code. These retry cycles—fed with specific analyzer-generated hints—might enable the LLM to repair and complete scripts. Logging those cases could also feed into refining the system prompts for the language itself.

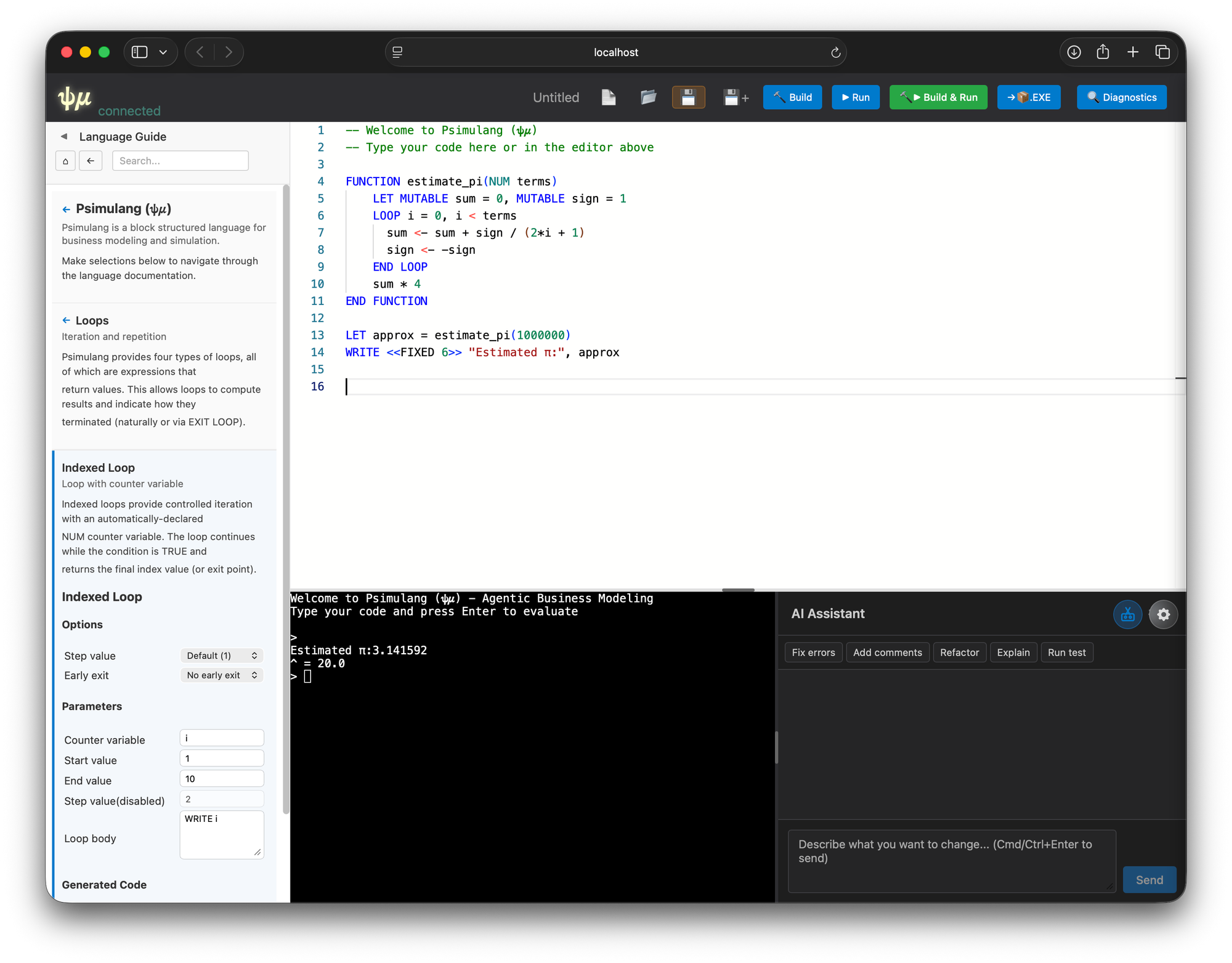

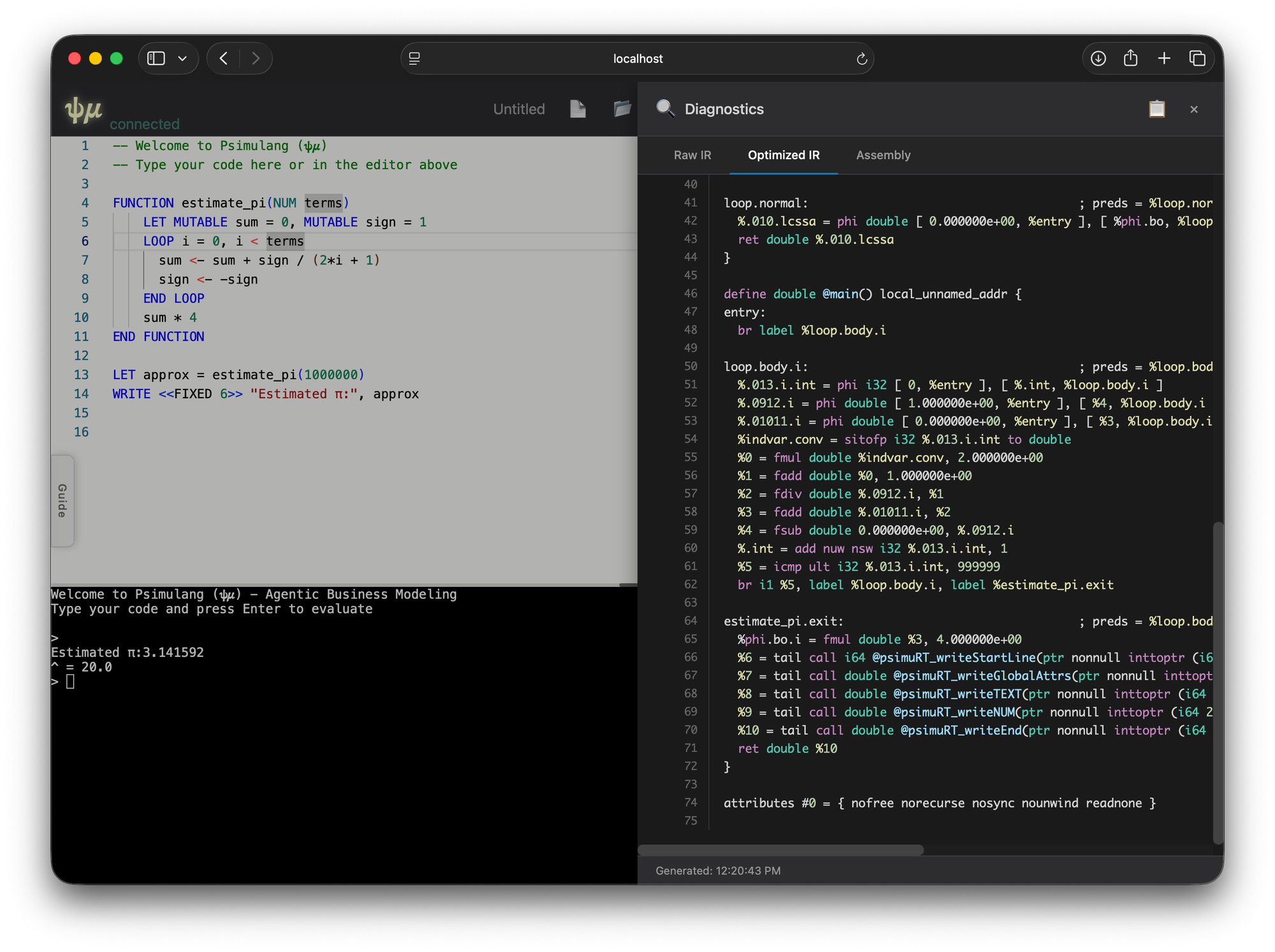

The language is called psimulang (originally chosen to evoke business modelling and simulation—revealing what was once a distant ambition). It also conveniently allows the two-character glyph abbreviation 𝜓𝜇 as a logo. LLVM, for its part, has been a surprisingly pleasant ecosystem to work in: its JIT makes it easy to get early dopamine hits from a small compiler that can produce native executables and run a REPL. The cross-architecture, cross-platform nature of LLVM is another boost.

The original project consisted mainly of:

- A parser producing a type-free AST

- An analyser producing a typed AST

- A backend targeting LLVM

- A small runtime providing a managed heap and built-in intrinsic functions

The runtime was linked directly into the compiler for REPL mode, and built as a dynamic library for compiled executables. All of this was hand-written in Haskell using LLVM v9 bindings available at the time.

LET TripleCount = 0, maxN = 1000

WRITE "Searching for pythagorian triples for integer side lengths 1 <= n

<= " maxN <BRIEF>

LOOP x = 1, x <= maxN

LOOP y = 1, y <= maxN

LOOP z = 1, z <= maxN

WHEN x * x + y * y = z * z THEN

WRITE <<BRIEF>> "(" x <WIDTH 3, COLOR blue> "," y <WIDTH 3, COLOR

green> "," z <WIDTH 5, COLOR red> ") is a pythagorian triple"

TripleCount <- TripleCount + 1

END WHEN

END LOOP

END LOOP

END LOOP

WRITE "We found a total of " TripleCount <BOLD> " triples."A pythagorean triple finder written as top-level psimulang

My first proper foray into AI-assisted coding was with the plain ChatGPT interface—long before agentics, TODO panes, canvas tooling, or file-aware workflows existed. It was simply the conversational UI. Coding with this was, frankly, frustrating, though undeniably interesting. You felt the small context window acutely, and you acted as the shuttle between ChatGPT and your IDE, usually with both open side-by-side. Cutting one’s teeth on tools that raw provides a strong anchor for appreciating what exists today.

The workflow looked something like this:

- Write the new feature description in a text editor (keeping the original goals was more valuable then than now, but remains good practice).

- Decide which source files the LLM needed to see in order to reason about adjacent interfaces, patterns, or styles.

- Paste the description into ChatGPT along with a prelude specifying stylistic conventions, libraries, extensions, etc.

- Upload the context files.

- Wait for generated code (thankfully inside a code block).

- Copy and paste the result into the project.

- Recompile (Haskell’s type system is good at catching mistakes).

- Paste compiler errors back into ChatGPT.

- Repeat.

There were, unsurprisingly, many gotchas:

- The small context window would fill, forcing a session reset and the need for the textual equivalent of a TV-show recap: “Previously on Best Feature Ever…”.

- The LLM could lose track of goals or constraints because of recency bias in the context window. This led to the familiar “I’m sorry, I…” corrections.

- Making a quick manual fix in your IDE—but forgetting to tell the LLM—risked creating an endless loop where it reintroduces the same error later.

Despite this crude process, I managed to upgrade the project from LLVM v9 to v12 and finally v15—spanning the major transition from typed to opaque pointers. This required introducing a backend type environment to track pointer referents so LLVM codegen could emit correct IR.

That work was non-trivial, and the letterbox-like workflow encouraged me to build the upgraded backend in parallel modules so I could toggle between known-good older versions and speculative AI-modified versions.

Quality and pathologies

Overall code quality was mediocre. This was likely influenced by the use of Haskell, which has comparatively lower representation in model training corpora. Errors were common: imagined functions, made-up library calls, and difficulty with advanced Haskell idioms. Haskell’s compile-time checking was a lifesaver, but there were many cycles of back-and-forth remediation.

Pathologies I saw often then (and much less now):

- Oscillation between a small set of patterns, none correct, with no convergence.

- Fixation on repairing errors the wrong way, going deeper into nonsense.

- Hallucinated closure, where the LLM insists the problem isn’t real and declares a broken solution “done”.

The last two still occasionally appear in modern tools. The oscillation pattern has become rare.

Claude’s early “artifacts” era

After this early ChatGPT work, I tried Claude, which at the time had gained a reputation for coding. Its “artifacts” feature—separating generated files from the conversation—felt like a major usability step. It supported incremental edits and versioning, making iterative refinement smoother.

To test Claude, I had it build a TUI for psimulang using the Brick library. I provided:

- A feature description

- A small working Brick example from another project

- The Brick repository URL

Claude entered a familiar oscillation pattern—this time between variants of outdated Brick API usage. Despite having correct examples, it was evidently anchored to patterns prevalent in its training corpus. A small amount of hand-written corrective code and explanation snapped it out of the loop, after which progress became steady.

I also learned something important: LLMs strongly gravitate toward volumetrically common idioms. In Haskell’s case:

- Defaulting to String instead of Text

- Preferring lists over Map/Set

- Ignoring STM in favour of IORef

This isn’t unique to Haskell—every language has this effect—but it’s something that users must proactively steer.

A few months later, with more time available and the emergence of Claude Code, I decided to use it to build a full web-based mini-IDE for psimulang. This was a significant upgrade in tooling power, so I expanded my process.

Before writing any code, I dedicated a session to refining requirements and producing a detailed implementation plan that included:

- Requirements and constraints

- Technology choices

- Design invariants

- A multi-phase development schedule

- Per-phase tests and reports

- Final integration tests and documentation deliverables

Using Claude Code was a revelation—a completely different experience from the conversational UI. It tightly integrated:

- The state of the codebase

- The LLM’s reasoning and generation

- Agentic abilities including tool use and web access

It felt like the first genuinely cohesive agentic coding environment.

Building the initial IDE skeleton

I outlined a modern web client:

- Monaco editor with psimulang language support

- REPL window supporting ANSI escapes

- Right slide-out diagnostics panel

- Left slide-out documentation viewer

- Yesod subsite architecture with the ability to run standalone or be embedded

- Websocket communication

- Multi-session support, optionally user-aware

Claude produced a functional initial version within minutes—astonishingly complete. With minor fixes (panel sizing, some Monaco quirks), the system became usable within an hour.

Advanced features: documentation viewer, search, templates

I then had Claude create a folding/expanding documentation viewer with search navigation. This was finished in about an hour. Next came a templating mechanism for injecting parameterised snippets into the editor. This took longer and involved some regressive steps, but still reached a very satisfying result.

This phase exposed an important trap: Claude’s context-compaction system.

As conversations grow long, compactions become more frequent and yield diminishing returns. Eventually progress becomes impossible. The lesson: recognise when a session is “too old” and proactively restart it. Ideally, have the LLM generate a continuation prompt summarising state and linking back to the spec to allow a clean, high-context restart.

The agentic layer and the “cul-de-sac” problem

Finally, I asked Claude to design and implement an agentic coding layer: a panel for conversing with the LLM, configurable to use local or remote models, with a mechanism allowing the enclosing Yesod application (when embedded as a subsite) to register handler hooks. This required careful specification: the backend needed to route websocket messages either to psimulang’s own handlers or to those provided by the parent application.

Claude initially seemed to interpret the spec correctly and began modifying the right files. But once I started testing, it became clear it had misunderstood a key requirement: it conflated “local vs remote LLM choice” with “whether hooks are registered.” The settings UI hid or showed the wrong options.

Correcting this proved unexpectedly hard. Even after identifying the mistake, the LLM repeatedly produced partial fixes or reintroduced incorrect logic. It was the first major case I’d encountered where the model struggled to back out of a misconceived design path.

This raised an interesting decision point:

When an LLM has mis-designed something, should you:

- Keep iterating forward and try to correct it in place?

- Revert to a clean commit and restart with a clarified specification?

- Restart the LLM session entirely (to regain context window)?

Each option has different trade-offs. On this occasion, I opted to “plough on,” hoping to preserve the value of earlier discussion. It ultimately worked, but painfully.

When Claude finally declared the job complete, I performed my habitual “global code review” request—only to discover that it had kept the old code paths in place “for backward compatibility.” Another lesson: unless instructed, LLMs will often assume that legacy code must be preserved. They rarely take the initiative to remove superseded logic unless prompted. This can quietly accumulate cruft.

The takeaway:

Ask explicitly for a final pass that removes vestigial or obsolete code paths and ensures the codebase is clean and idiomatic.

Or perform that cleanup yourself before merging.